I’m partially retired from cons, but when I used to table at them, starry-eyed future comic book writers would ask me about writing comics. I was even known to present a panel or two about it. After reflecting on comic book writing for a couple years, I have come to the conclusion that writing comics is a lot like when I was young and I was learning how to become a mechanic. I had to study hard and get hands on experience.

Study Hard

To become a mechanic, I had to study hard. I needed to know all the parts of a car, what each one did, how they worked together, and what made it run right. Writing comics is very similar. You need to know all the parts of the story structure, how the elements of comics (art, story, and lettering) come together, and what makes a comic story “work.”

The story structure of comics can be different from writing a film, a prose story, or even a poem. Comics are often serialized like a television show. Think of any show, the DC or Marvel comics TV shows, Game of Thrones, even Parks & Recreation. Each episode has the elements of a plot: exposition, minor conflict, rising action, and climax. There’s a minor resolution usually followed by a cliffhanger to get you to tune in next week. Each episode builds on an overall story which moves the overall arching plot forward to a goal at the end of the season. Comics often use this same format. Just like on TV seasons. The major resolution at the end of the season leaves enough open for the next season and can even end on a cliffhanger to keep fans speculating on message boards and social media until the new season comes out just like when a comic book miniseries ends.

When I first started writing, it took me awhile to balance out all the elements that make up a comic. I grew up reading comics, but writing is a whole new ball game (or manufacturer is we’re keeping with my car metaphor). Unlike a film or a movie with moving pictures, comics are like a series of photos (panels) that tell a story.

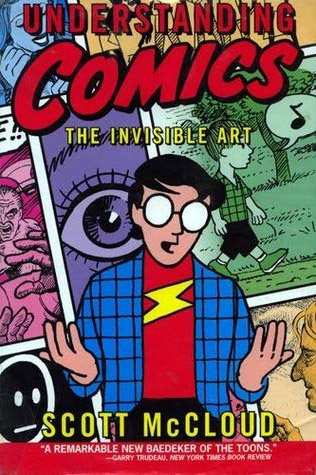

For example, in a comic if you see a boy in a little league uniform wearing a mitt as he looks up nervously, then in the next panel you see him holding up the ball triumphantly, it tells a story. You know that he was probably in the outfield and the ball was hit towards him. He was unsure of himself, but he caught it. You never saw the panel (like you probably would in a movie or TV show), but you knew he caught it. When I first started writing comics I made the rookie mistake of writing an entire “scene” into one panel. I would often write something like “Panel One: The little leaguer is nervous as he looks up, but he catches the ball and is carried off the end on the shoulders of his teammates.” I probably drove a lot of artists crazy trying to figure out how to capture all that into a panel before I realized that each panel is a picture, not a movie scene. Scott McCloud explains this perfectly in his book, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. This is one of the first scholarly works that looks at comics as a legitimate story telling medium and art form. Plus, the whole thing is a comic book itself. I recommend that everyone starts by reading it. Read it before you write your first script. It will help to explain comics better than I ever could.

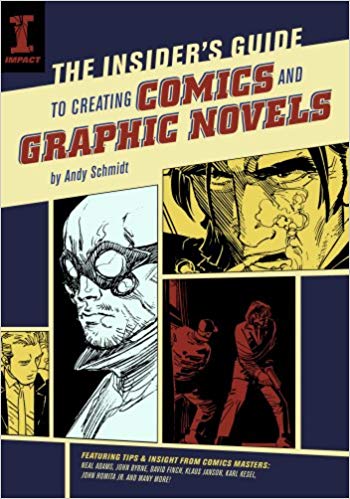

Another thing to keep in mind is that every bit of dialog, be it from a character or a diegetic narrator, must fit into the panels of the comics while still leaving enough room for the art to tell the story. It is best to keep that in mind when writing dialog. Just like when writing a poem, the dialog should be as condensed and sparse as you can make it while still conveying the message to the reader. Comics really are a balancing act between prose and images. Sometimes you can have more of one than the other, but it’s best to keep them balanced. Andy Schmidt does very well describing how to balance all these elements and how to lay out panels in his book, The Insider’s Guide to Creating Comics and Graphic Novels.

The last part of studying you’ve probably already been doing. It’s to read comics. Think about your favorite comic? What do you like about it? Maybe you buy it because it’s your favorite character. Even comics with your favorite character has some stories that are better than others. What made some of them worse than others? In order to prepare yourself to write comics become an active reader. Analyze what the artist and writer did well individually. What did they do well together? Can see spots where they weren’t in sync? You might find the faults immediately while it’s a lot more difficult to pinpoint what made the good parts work so well (which is normal).

Hands on Experience

Once you understand what each part does, how they work together, and what makes the comics “engine” run (getting back to the car metaphor), it’s time to roll up your sleeves and write your script.

Before I start writing the actual script, I usually write out the beats to the story. The beats are just things that you want in the script. It can be important events in the story, character notes (what they’re thinking, feeling, wearing at certain points), and dialog. Pretty much anything you want to remember when you write the actual script.

Writing out beats and/or a rough outline is very important when writing comics. Unlike prose writing, you have a very limited page count to work with. Most book publishers don’t care if your novel is 500 pages or 750 pages. However, comic book companies have a budgeted amount to pay the writer, artist, inker, colorist, and the letter for each page. You can’t go over that page count and you must tell the story within that amount of space.

Practice Makes Perfect

I remember how proud I was when I wrote my first comic book. Looking back on it, I can’t believe all the things I did wrong (I’d like to say my early days as a mechanic were different, but I’d be lying). We all get into the comics business because of our love for the medium, so have fun and try to remember that feeling you had when you read your first comic.

Write a comment